Kathleen Henderson at 18th Street, by Jessica Hough

Kathleen Henderson at 18th Street

By Jessica Hough

Kathleen Henderson in her studio at 18th Street Art Center in January 2021. Photo: Sean Meredith.

On January 6 when news alerts lit up our smartphones that rioters had breached the Capitol building, Kathleen Henderson’s studio at 18th Street Art Center was already crowded with goons. They had followed her, as they always do, and were taking shape on her easel and in drawings hanging four rows high.

For close to twenty years, Henderson has been giving form to characters with a doughy human-like shape but vacant eyes and gruesome smiles. These blobby phantoms, rendered in oil stick on paper, inhabit corporate offices and take the stage at large events. They carry guns and stumble through forests meddling with wild animals. They limp along in a human-ish way but embody only our lesser qualities: narcissism, a mob mindset, and a blind appetite for power. Henserson’s surrogates expose these human qualities that spell our doom. “The problem is us. It's hard to solve,” she says during my visit.

I’ve been following Henderson’s work for a dozen years, and on that January day when I clicked through to footage of a mob pushing through police barricades and saw photos of men clamoring through the broken windows of our Capitol, it seemed to me that Henderson’s drawings had finally come to life. Dressed in thick quilted coats and knit caps that softened the shapes of their bodies, carrying weapons and flags, and costumed in furs and horns, I saw the goons that Henderson has been cautioning us against.

Henderson jokingly refers to her time at 18th Street as her “doomsday residency”; first with Covid to contend with, followed by the attempted coup. The usual camaraderie of the Santa Monica studios was replaced during this time with an unsettling quiet that kept her frightened by the noise of the building settling at night, and the muffled voices of people passing on the sidewalk outside her studio. Many of us were paralyzed witnessing the Capitol siege, and Henderson too was initially struck into stillness. But she routinely makes work that operates in the space of doomsday. So in the end, her residency at 18th Street turned into a generative time. Working with news radio playing in the background, this latest crisis was telegraphed through her hand in drawing after drawing.

Unaccustomed to having long uninterrupted periods at her easel, she found herself reading and writing during much of the daytime. In the evening, when her ideas were stored up, even pent up in her mind, she released them to paper. “So much of making art is like a transference of energy,” she tells me, and that energy needs to build. Henderson’s drawings are electrified by the jerky quality of her line work. It animates her characters, and delivers a discomforting tenor to the viewer.

The drawings look like they’ve been made quickly and they have, but her process is one where she makes drawing after drawing until she feels she’s gotten it right. She tears up the ones that she feels aren’t working. “I know when I don’t have it,” she says. Lifting the lid of a ream of paper she brought with her, only a few remain of the 100 sheets she started with. At home, her easel sits in a corner of her cramped bedroom with finished drawings going into a box under her bed with little possibility of being evaluated in the moment. The vast studio at 18th Street allowed her space to pin the works up, look at them in relation to each other, and consider them as she went. This was an indulgence that fed her productivity.

In one drawing, a massive blob man with saggy breasts rides along a parade route bolstered by the energy of the crowd. His naked form rises up from an open top vehicle; his mouth agape. But the dominant gesture is the stiffened arm pointing with violent accusation to someone in the crowd. It’s not hard to imagine who Henderson might be describing. These human stand-ins get their power, in part, from conspiring, whispering, gathering in groups. And in Henderson’s drawings, they appear to go unchallenged.

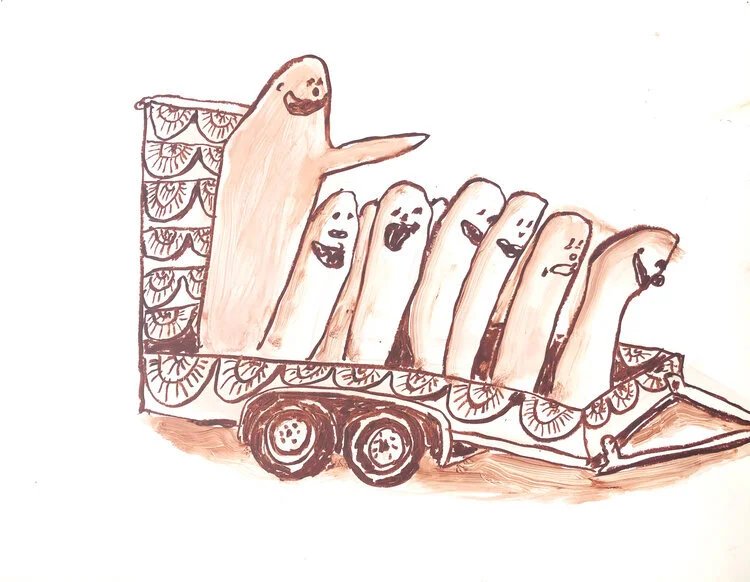

Some of the characters that took shape during her residency are reduced to an even simpler form--empty, oblong shmoos. Unclothed, they are turds or “shits” (which is how Henderson describes them). In one drawing, a parade float draped in festive bunting that you might expect to carry a small-town elected official and a handful of girl scouts is instead tightly packed with smiling turds. Parading, flag waving, (and pointing) runs through these new works; the superficial elements of leadership.

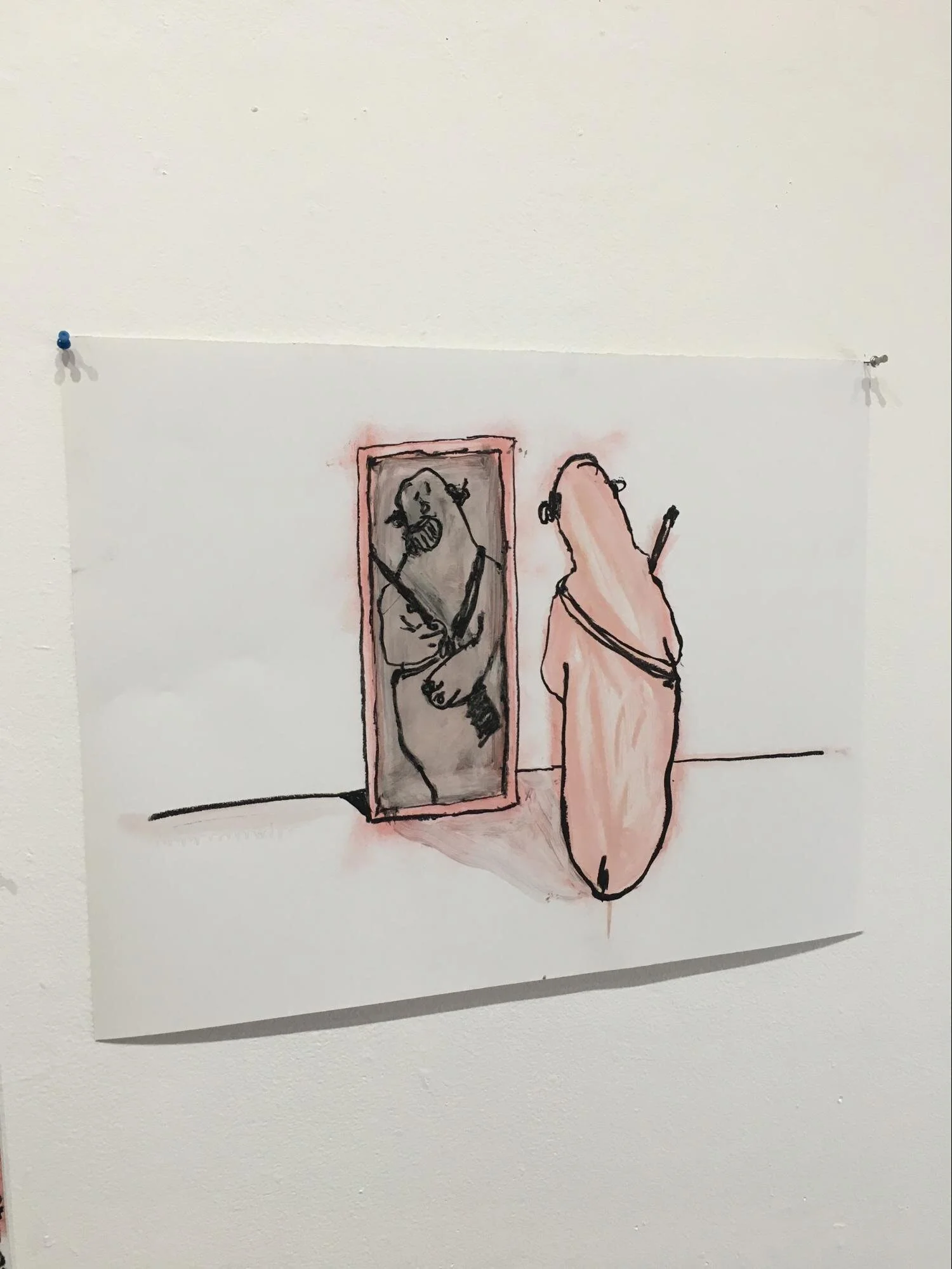

Henderson’s work uses satire but the critique is so broad as to encompass us all. Her drawings are funny but only for the split second they need to disarm you, before they burn and weigh on your conscience. We smile until we know that they’re about us. In another drawing, an armed turd ponders his reflection, easily reminding us of the selfies insurgents posted to social media to memorialize their violent invasion of the Capitol. The turd isn’t me, you think. But it is.